I make it no secret that I have a strange hobby. People are always either impressed, surprised, or confused when I describe to them what I enjoy doing in my spare time. It’s not like it’s that different from other hobbies which people have; some people make models of trains; some people made digital models of real-life systems.

I am making a futuristic starship simulator.

I mean make in a very loose sense. This is hardly my project, and I am hardly a contributor at all. But the small part I am playing is certainly an integral role in the process. So far, I’ve had a say in the software controls, the universe which the simulator will operate in, the lighting and sound system layout of the simulator set, and some of the custom hardware integration which we will be using.

I might be getting ahead of myself, though. I suppose I had better take a step back and explain the whole process from top to bottom.

This is Victor Williamson. Inspired by Star Trek, and seeing the benefits of simulated education early on in his career, he pioneered the concept of using science fiction simulations to teach Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM). Early on, he would do simple role-plays where his students would push paper buttons on cardboard boxes and he would react by narrating a story using his vast collection of false accents and an overhead projector. His first flights were recon missions to Mars where they would skim the surface, talking about the nature of the Red Planet. Students were interested, but not really excited. So he figured he would spice things up.

He had a Romulan ship attack them.

It worked. By adding in that bit of drama, the kids were suddenly glued to their chairs, their minds fixed on the simulation. He would go on to craft ‘missions’ like this one which revolved around a main story point, but also featured a prominent science topic: negotiating with the Romulans to go and study a Supernova; passing by a black hole and dealing with the relativistic effects; deciding what to do with an escaped slave who emerged from a wormhole. Adding the artistic elements (turning STEM to STEAM) helped to round out the missions and keep the kids interested. Lots of good fortune and several thousand dollars of grant money later, and a permanent simulator was built in his school’s back lot.

And thus the Space Center was born.

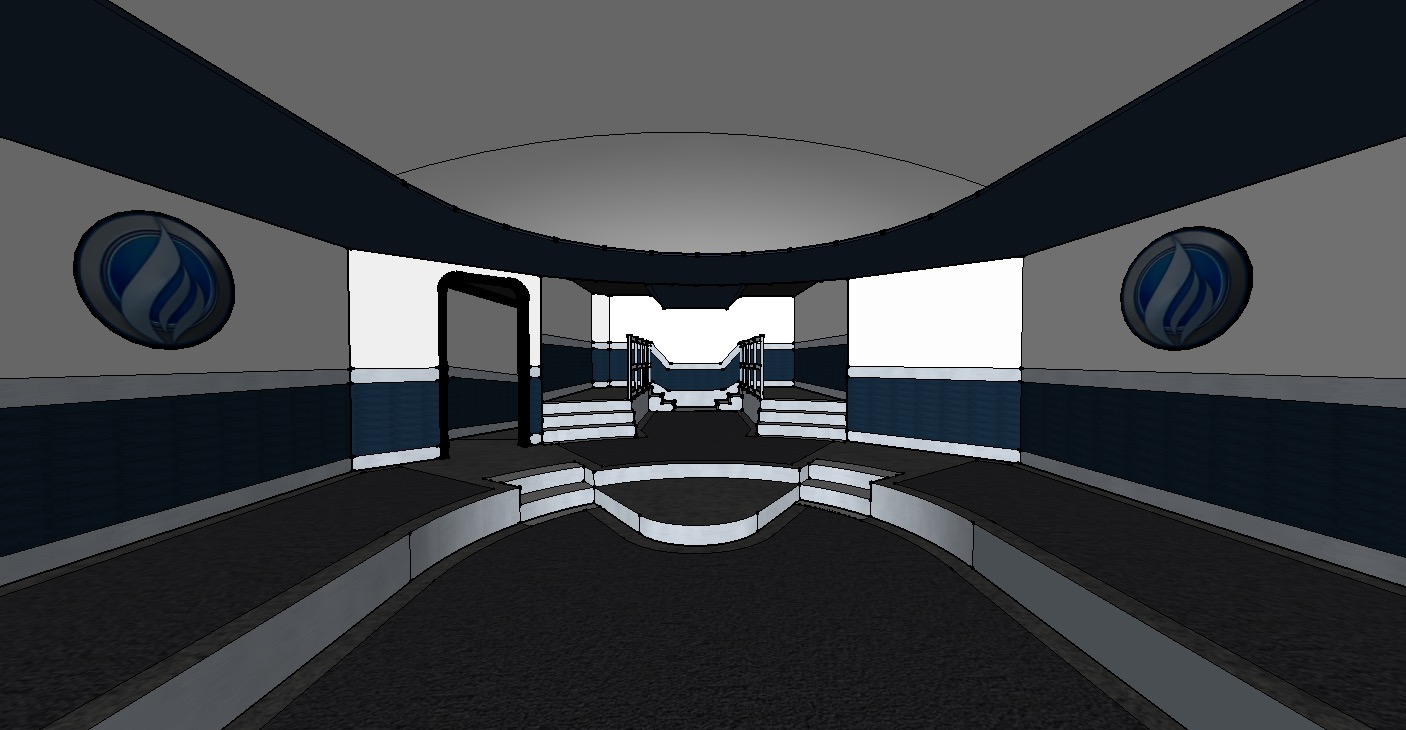

The Voyager was built in 1990, the first of six ships built at Central School (the last of which was built in 2005). The image above is how the flagship looked shortly before it was shut down in 2012. For 22 years, this ship was the stage of space dramas teaching school kids teamwork, leadership, math, science, communication, responsibility, and decision making. It was a classroom, laboratory, and summer camp destination.

While the Voyager was open, the Space Center was also the central hub of a bustling volunteer organization. Hundreds of students impressed and inspired by the field trip experience on one of these ships would become even more involved. I was one of them.

I was so fascinated with the experience of the Space Center that I made no delay in beginning my work as a volunteer. I had come to the Space Center many times with my older brother, who was already a volunteer, and was blown away at what happened behind the scenes that I knew I had to become part of it.

I put in my volunteer registration papers in 2006, and began the process of observing and volunteering. I saw the control rooms, the skilled Flight Directors in charge of the flights (and which I always wanted to become), the supervisors assisting and monitoring the crews, the volunteers performing acting parts and running computer stations.

My brother, Brent, was a programmer, so naturally I would join with them. These programmers would meet at least weekly to work on the next cool computer terminal or software controlled gadget. The meetings were truly amazing. None of the members of this ‘Programming Guild’ were even out of high school, and yet every week there would be some new, amazing idea for something to put into a simulator. An integrated video system for creating video playlists for the missions; a fluid set of controls, which would allow you to put any screen on any computer; a sound effects player which integrated into the controls to react to what the kids were doing; a push server architecture. Some of these things would be discussed, even prototypes made. But none of us were skilled enough to be able to build it all. Over time, the programmers moved on to bigger and better things, leaving me as the lone remnant of that guild.

I eventually did reach my dream of becoming a Flight Director, and found it to be one of the most fulfilling and powerful experiences of my life up to that point. As Flight Director, I was in charge of representing the Space Center to the students who came. I would brief them on their mission, train them on how to use the simulator, launch them into space, play the role of all the aliens they came in contact with, play the mood music and sound effects and video and tactical view screens and interact with their computer stations and direct my volunteers and actors to do the various things which they needed to do… it was a lot of work. But in addition to doing all those things to put on a good show, I tried my best to remember that this was an educational venture (or EdVenture as we like to call it), so I mixed in the science, math, and social studies as much as possible.

I also became a full-fledged programmer, and started working on creating new simulator controls. One by one, I re-programmed each of the Space Center simulators (excepting the Voyager) using the new Revolution programming environment. Many of the ideas which were first brought up in the programming meetings were implemented in these controls. Truth be told, though, they were buggy and not entirely functional. There was so much more that they could be, given time, resources, and experience.

When the former Set Director, or simulator manager, of the ship I ran left on a mission to Korea, I was placed in charge. Suddenly I was responsible for an entire starship simulator. In the weeks following, me and my co-director Bracken Funk did some major modifications and renovations to the ship. I tore that ship apart and put it back together, learning how it worked.

I learned how the networking ran through conduit, and I even pulled my own cables through to set up a phone in the front of the ship. I learned how the audio inputs fed into the mixer, which fed into the amp which ran out to all the speakers, and I even added a few more speakers to the mix. I learned how the video systems converged to two switcher boxes, and the output of those ran to the main view screens on the ship, and then, out of necessity, learned how to set up a RGB Component video system (it had a funny glitch, though, where the signal would cut out whenever you switched inputs, returning after a few seconds of blackness). I did some custom electrical wiring to create a smoke machine timer, a transporter light, and a strobe light spark effect. This little ship pushed the boundaries of what kinds of effects we could pull in simulators.

Also, working off of the groundwork laid by my brother, I installed a DMX (computer controlled) lighting system in the Galileo simulator. This allowed the lights to be turned on, off, switched from red to white, and shaken (during an explosion) with the mere push of a button. This was an exciting time.

I left the Space Center officially in August of 2011 when I moved to Provo to attend BYU. I knew that I wouldn’t have the means necessary to be coming to and from the Space Center to program and fix bugs, and I needed to let my successor get his feet wet without me hovering behind him. I left on my mission in January of 2012.

August of 2012 brought the closure of the Space Center by the Alpine School District for renovations. By October, there was no sign of the Space Center ever re-opening and a political campaign was founded to fight the District’s decision and bring the Space Center back. This campaign was successful to an extent. In time, the District caved and began to perform the necessary remodeling. However, the original Voyager simulator (by far the most impressive and attractive of the five) was deemed too much of a hazard to be retrofitted, and was closed permanently.

I got the chance to see the Voyager after I got home from my mission. It was hardly a shell of it’s former glory. Dust was everywhere; random implements were strewn all over the place. The desks, void of computers, revealed the plywood which was concealed within. I remembered going up those spiral stairs, exploring the Captain’s loft, working from the Engineering platform or sleeping in the bunks on Deck 2. Now all of those things were either gone or boarded up. Nothing was left except memories.

During this time, Victor, who had been director of the Space Center from when it opened to when it closed, moved from Central to another elementary school, and eventually retired completely. Not too long afterward, though, he was approached by Renaissance Academy, a charter school in northern Utah County, and asked if he wanted to make a space simulator for that school. He accepted.

Since then, a group of Space Center volunteer alumni have joined together to create what we call the Farpoint Creative Team. This team is a band of some of the Space Center’s skilled and talented volunteers who have gone on to get degrees and training. Helping to construct this new simulator is our way of giving back.

It’s remarkable who we have on the team. Of course, Victor is the visionary leader and chief educator. We also have science fiction and astronomy experts; a data analyst, graphic designer, and expert flight director; an architect; an engineer; medical professionals; and programmers (my brother and myself). All of us bring something unique to the table, and all of us together, pooling our resources, think we’ll be able to make the most impressive, most immersive experience ever. Not only that, but also an environment where learning will happen organically.

There was a little bit of debate about what we were going to call the new ship. Vanguard was a name that was sticking for a time. However, much to the approval of the team as a whole, we decided on something better.

The new ship will be called Voyager.

I joined the Farpoint Creative team on accident almost. I was home from my mission for one short week before I got the itch to return to flying space ships. Even more surprising was my desire to program again - I didn’t think it would be something I ever wanted to do again.

My brother had told me a lot about the new controls which he was building for this new simulator which was being constructed. He called his controls framework ‘Flint’, and it was designed to be a complete software solution to everything in a space simulator. The whole system was designed to be modular, allowing you to add or remove screens, stations, utilities, and functions as needed. It also meant that adding new functionality was as simple and making the one isolated package and including it with the rest of the system.

Flint is built on some cutting-edge software which was hardly even dreamed of when I had left on my mission, let alone being a reality. Now, all of the things which I had always wanted as a flight director were at my fingertips: Software controlled lighting, sound effects, audio, music, video, and other effects were now all possible; the ability to redistribute the entire simulator on the fly; controls which could be added to and improved over time, part by part; blazing-fast 3d animations. All of that is only the beginning.

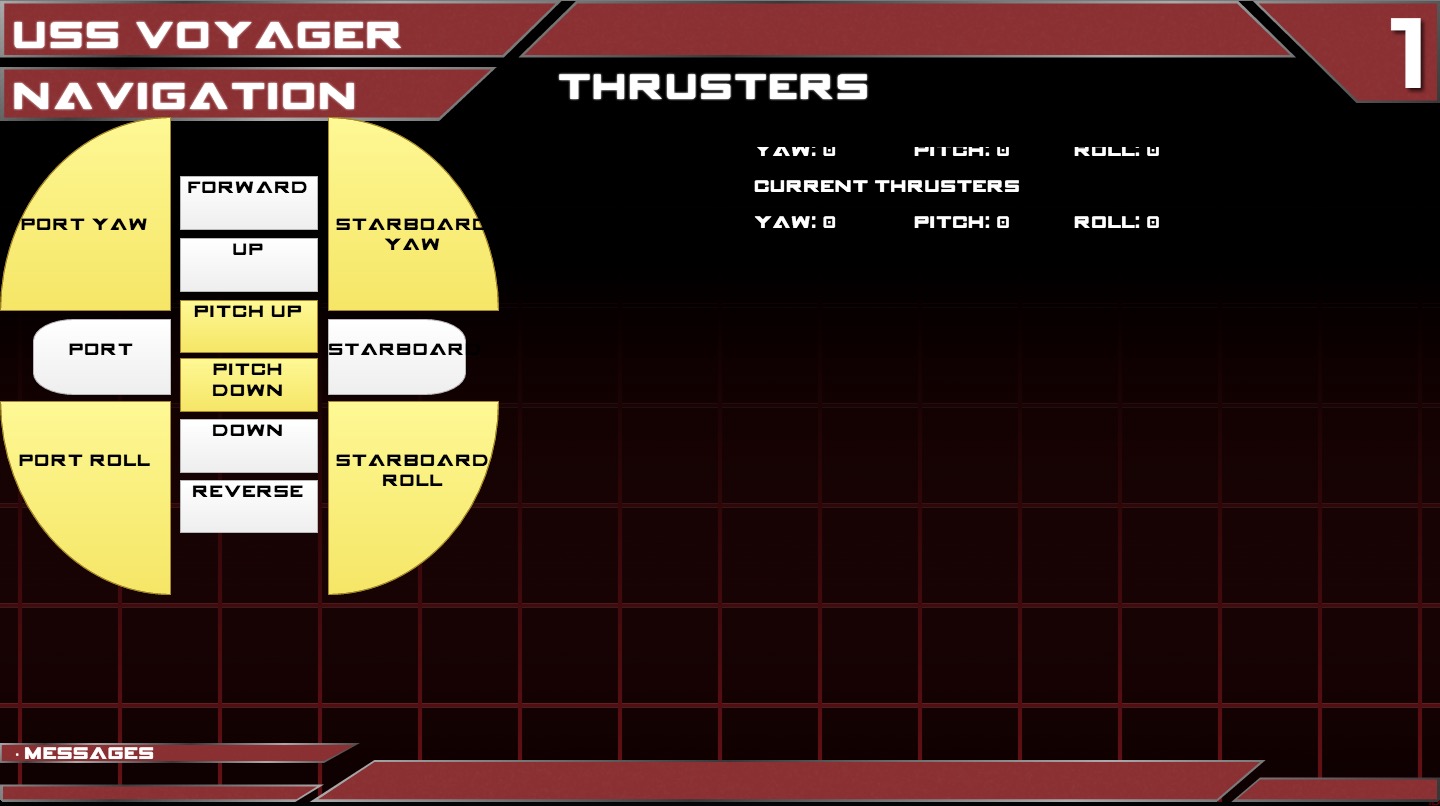

And, of course, my beginning was a pretty far cry from all that. The first screen which I programmed for Flint was the Thrusters - a direct copy of the old Voyager’s controls. You press a white button and you move in a specific direction; the yellow buttons rotate the ship. It took me a little while to actually program the screen. I had hardly touched Javascript (the language Flint is written in) before my mission, and the new framework had a bit of a learning curve. In the end, though, I had a completely functional thruster card.

This was just the beginning.

My work was eventually noticed by the rest of the team. I had begun tagging along to Space Center board meetings with Brent, my older brother, and during one meeting I showed off some of the things which I had developed. Vic invited me at that point become a full-fledged member of the creative team.

Ever since the close of the original Space Center and Victor being brought on to Renaissance, the goal has always been to build a new simulator. This wouldn’t be like the simulators of the past, though. It would be designed from the ground up for one main purpose: long duration missions. These serial missions would last months at a time, and focus on experimentation, experiences, and learning.

The simulator would also replace one of the computer labs, and as such would need to be usable and accessible during the day. All of the building code violations which closed the original Voyager simulator were taken into account, with specific consideration being given to accessibility for disabled students.

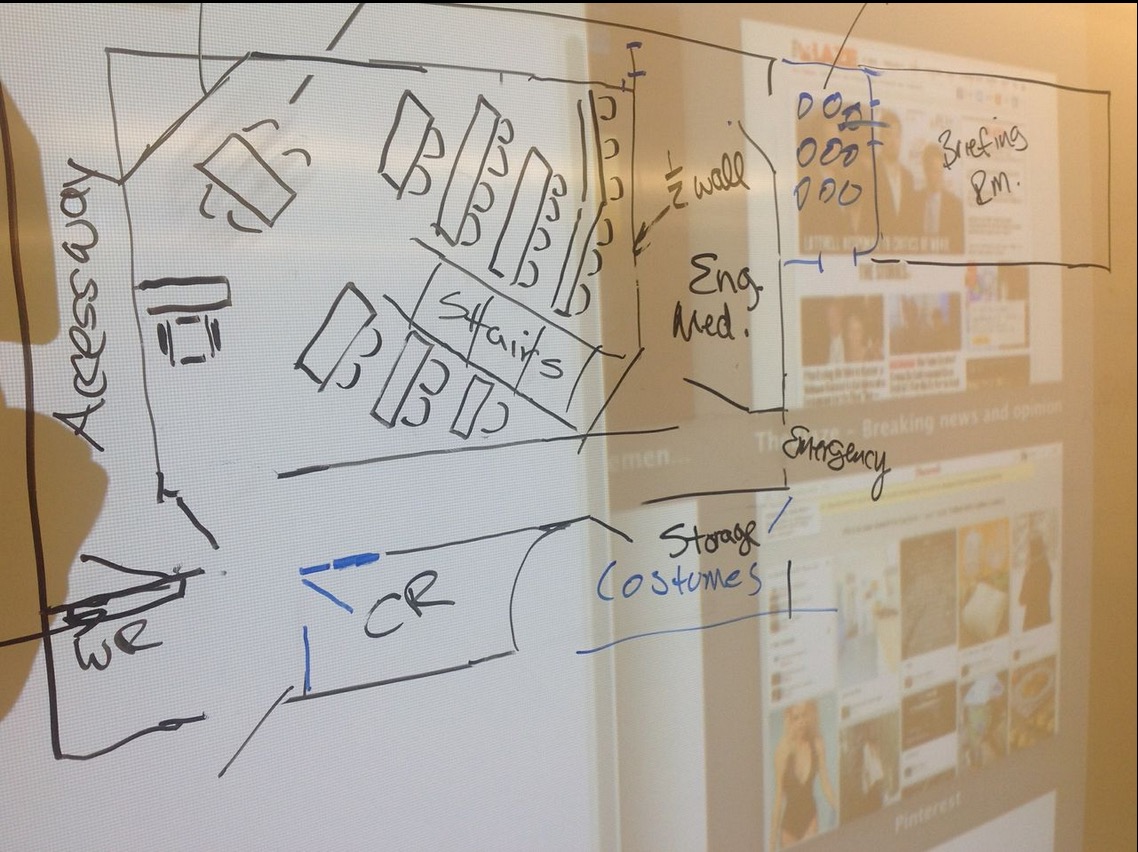

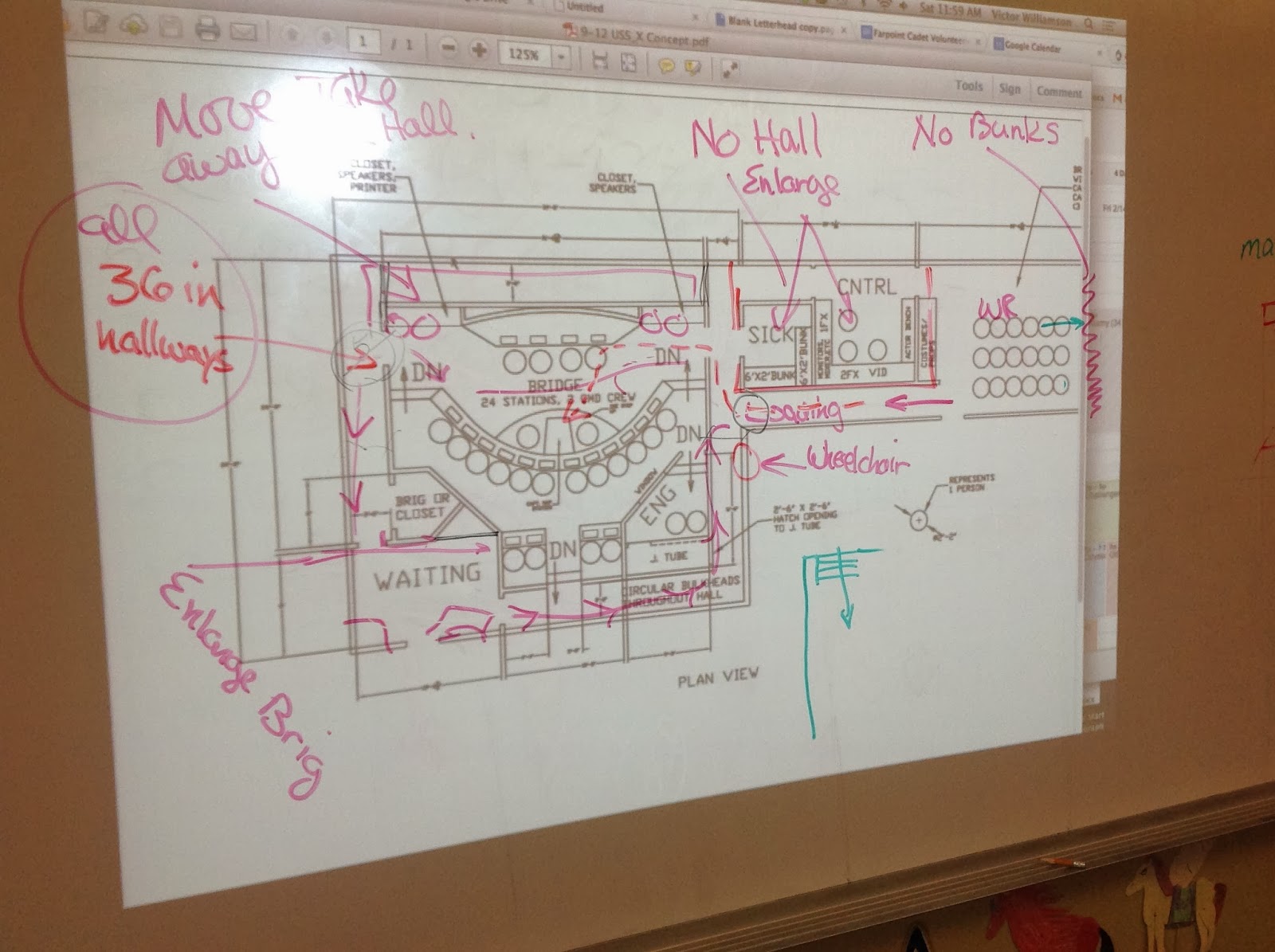

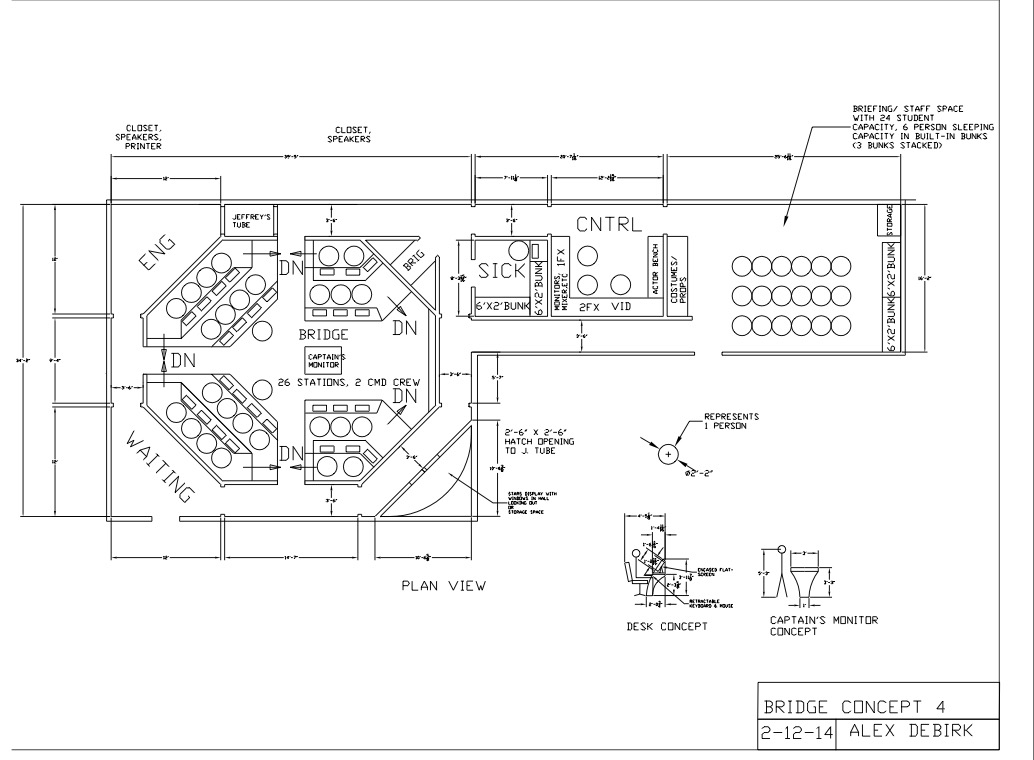

I remember some of the first creative meetings I went to were focused on architectural plans for the new simulator. Alex Debirk, a structural engineer and long-time flight director, had a few different versions of simulator plans, each with its own flair and style. His designs were limited by the space which was offered by the school and the number of students (26) which the room had to accommodate This only left a few options for placement of the bridge and control room areas.

Naturally, the best way to design a room is to case it out yourself.

This was one of the original designs which was discussed. This particular design took advantage of the massive space left over from the room which the ship would occupy. It included a separate sickbay and engineering room just off of the bridge, had a small brig, converted the classroom on the far right side into a briefing and conference room, took advantage of the exterior door with a waiting area, and was filled with hallways; perfect for alien invasions. Several different configurations of the main bridge were considered. However, it was eventually deemed to difficult to build. It would have required massive construction costs including demolition of several walls and two entire rooms.

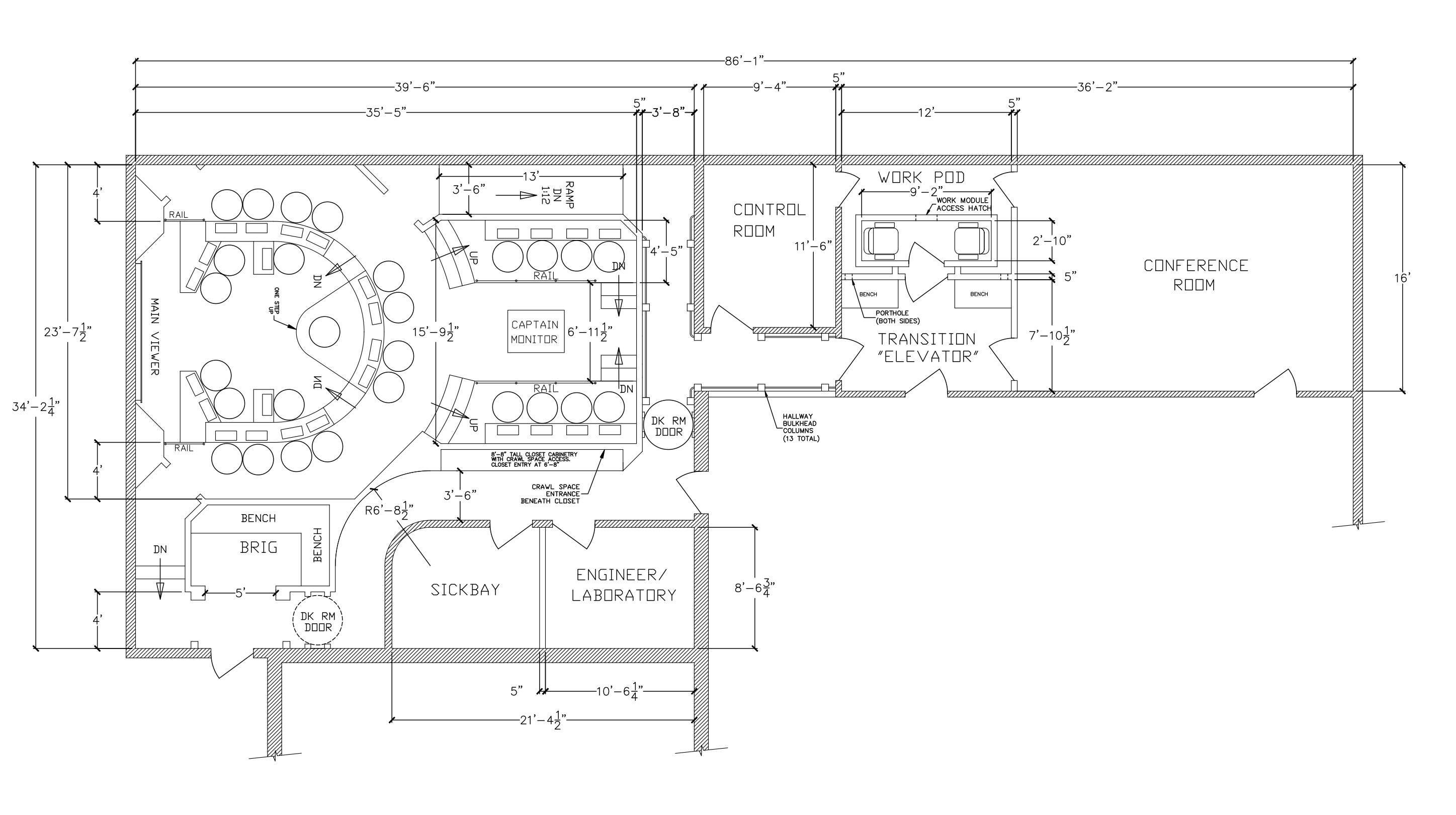

The objectives were changed to include leaving as much of the original construction as possible, with limited demolition. This drastically changed the designs, limiting what was capable in the space provided. However, Alex worked his magic and came up with this:

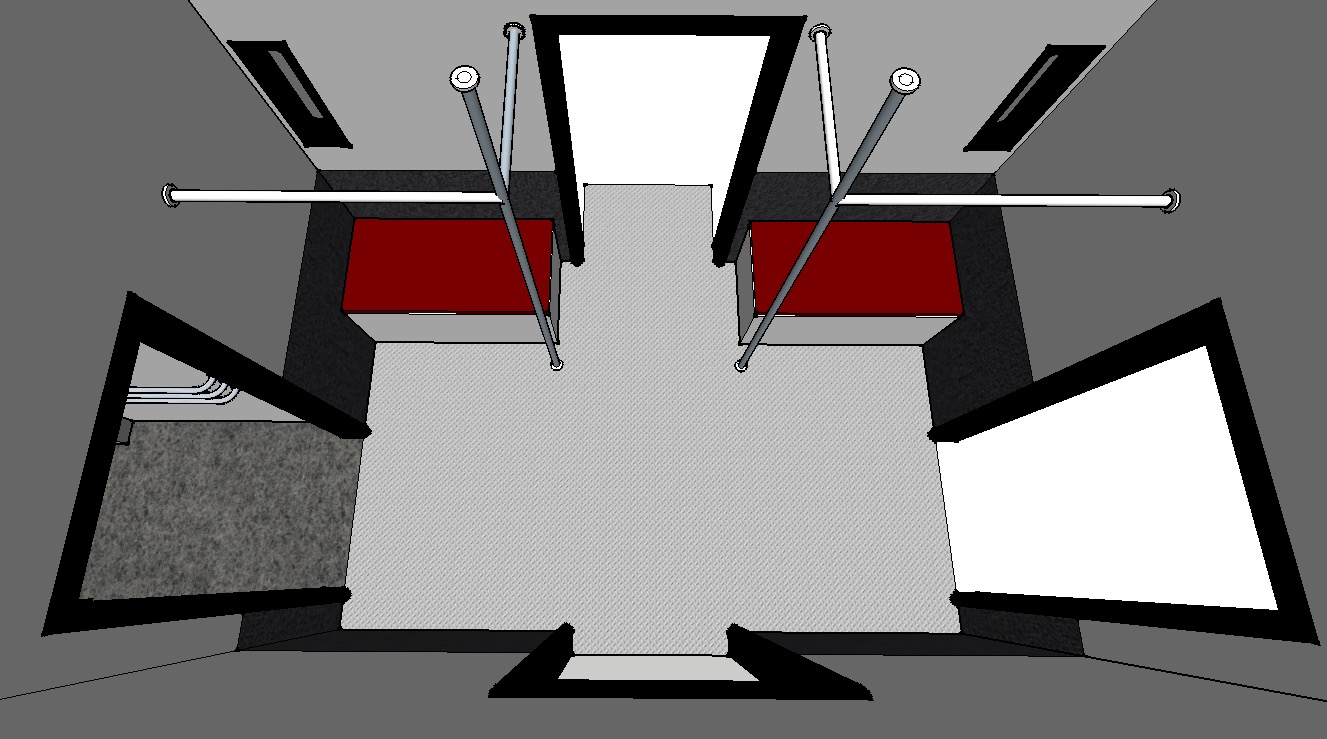

This is the final layout which was decided on, incorporating many of the positive aspects of the original design: Sickbay and Engineering are separate rooms, now located on a separate deck accessible through ‘turbolifts.’ The bridge has two separate possible entrances, allowing for multiple invasion vectors. The brig remained; the briefing room remained. The waiting area had to be nixed, but in exchange for that, a special, multi-purpose transition room was designed. Inspiration was drawn from subway cars. This ‘transpod’ is meant to act as a space elevator, shuttle craft, and crew teleporter, essentially a ‘room of requirement’ for getting the crew wherever they need to go. The hanging bars were an absolute must.

The hallways were spiffed up with full-height bulkheads along either side.

The bridge features curved front desks with two raised platforms on either side. Sadly, my picture omits the desk units. However, you can see the plans for a curved half-dome structure above the main portion of the bridge, which provides most of the lighting for the bridge through indirect light reflection. The captain’s station is elevated, and in the far back is the Captain’s Monitor (also not displayed). This is a table-top display which shows current tactical information, allows the captain to make plans, and features a multi-touch screen for drawing diagrams and interfacing with the computer.

The sickbay and engineering rooms are actually built into an existing storage room which is adjacent to the simulator, which adds both convenience and cost-savings.

An additional bonus is the inclusion of a ‘Workpod’ room, a special storage space dedicated to a mobile transport pod which the crew will be able to use to repair and upgrade their ship.

With the general plans in place, it was time to get to work on the more technical aspects of the ship. While every member of the team had invaluable contributions to every aspect of the simulator, I’ll focus on the parts which Brent and I directly affected.

We took responsibility for anything which carried a low-voltage data signal, namely sound, computers, camera surveillance, video, effects, and lighting control. I’ll touch on some of the decisions we made for each of these.

Sound

This ship is one of the most unique as far as sound goes. Unlike any other ship, it has multiple zones which each need to be able to play different sounds at different times. In addition, there need to be microphones placed in each of these separate places to ensure that the staff can hear what is going on there.

The first challenge was figuring out a way of taking a certain number of inputs (such as music, sound effects, ambiance, and microphone input) and sending them to different outputs (such as the main bridge, the hallways, the briefing room, or the sickbay and engineering rooms). As it turns out, this isn’t as easy as one would imagine.

Fortunately for us, a brand-spankin’-new (read July 2014 new) digital audio deck hit the shelves, and it has all the features we could ever need. It takes all the inputs and outputs we could want and route them wherever we tell them, has an onboard DSP for equalizer and audio effects, and is completely computer controllable. That means that all of the audio can be manipulated through Flint.

Imagine for a moment that the communications officer is making an external call. Instead of a phone system, the comm officer will have a headset hooked into the sound system. They will talk with someone in the control room over that headset. However, the instant they transfer that call to main speakers, the audio deck will switch the output from the comm officer’s headset to the main bridge speakers, and they will instantly be talking to everyone.

Or, the captain presses a button on his chair controls - “Bridge to Engineering”. Without hesitation, the bridge audio will be connected to Engineering, and the captain will be talking to Scotty, and vice versa. The possibilities are limitless.

Another challenge which was apparent was whether to do a passive or active speaker system. Passive is what most people think of when they hear about a sound system - all inputs route to an amplifier which then sends the powered signal to each of the speakers. However, for a ship with as many audio zones as we have, you would need at least 6 amps, which adds up quickly.

Instead, we opted for an active speaker system, one in which all of the speakers already have amplifiers inside of them - all you do is send signal directly to the speaker and it cranks it out for you. This way, instead of getting separate amps, we just send the signal straight from the audio deck to the speakers, cutting down on cost and complexity. Subwoofers will be placed underneath the raised floor of the bridge, allowing for sound to reverberate through the entire simulator.

Also, as I mentioned, headsets will be the way to go in this ship. There will still be a speaker and handheld microphones in the control room, but the flight director will also be able to use a personal headset, programmed to hear only what the flight director wants to hear and to speak only where the flight director wants to. This will provide additional flexibility to the flight director.

Cameras and Video

All camera and video data is being transmitted over Cat5e cable, simplifying the simulator extensively. The cameras are IP-PoE, which allows us to place them anywhere we want and access them from any computer. We also have talked about installing a new DVR and overhauling the entire schools camera system to run along side our cameras.

The video system is HDMI over Cat5e, mainly for simplifying our cable runs. Instead of using DVD players, this simulator will have its own dedicated video computer powered by Flint. Clips will be stored and then cued up based on which mission the simulator is doing. This also provides the flexibility for dynamic tactical cards - since everything is connected to Flint, tactical cards which are pertinent to the situation can be displayed (shields, communications, etc.) Also, the cameras are linked in too, which means that the captain and engineer could have both an audio and video conversation. In fact, the Flight Director could even get in on the conversation too with some special technologies which we are currently developing.

Lighting and Effects

DMX512 (Digital Multiplex) is the industry standard for theatrical lighting. It allows you 512 channels of lighting control, each channel with its own dimmer capable of being set to any value from 0% to 100% intensity. Magellan and Galileo use DMX lighting, both computer controlled.

Lighting in previous Space Center ships consisted of large panels of lighting controls with manual dimmers (for shaking the lights during explosions) and switches for changing between red lights and white lights (or blue, if you are the Phoenix). The lights themselves were incandescent can lights (or CFLs in the Magellan), tinted either blue or red for the accent lights. Some of the newer ships, such as the Odyssey II or some DSC ships, use RGB tape light, controlled via remote control. These tape lights have separate colors for red, green, and blue (combining them creates white light), and theoretically can produce any color of the spectrum. However, being remote controlled made them laggy and slow and limited the possibilities of color production. The lighting we chose was controlled by a DMX driver, meaning lighting changes are instantaneous, computer controlled, and each channel (red, green, and blue) and be set to any intensity individually, creating 16 million possibilities of color.

We opted for doing a system with RGB LED strip lights in addition to bright RGB PAR can fixtures to act as spotlights. Believe it or not, it’s really difficult to find cans which have the certifications necessary to be installed in a permanent location. Through our perusals of the internet, we managed to find something which was similar to our tape lighting, but in a retrofit can structure - basically designed to take the place of a normal can fixture in a home. Go figure, though - it wasn’t certified.

We continued our search until eventually we came across the mother-load; an RGBAW+UV PAR Can. Yep, you read that right: Red-Green-Blue-Amber-White+Ultra Violet. That’s six different types of LEDs which fit into this thing. Not only that but they come in two sizes, are 100% computer controllable, super bright, and individually addressable. Oh, and best of all: they are CE certified. We’re right now exploring what kinds of effects we can do with lights this beefy.

Effects & Interaction

Since the world has gone the direction of IoT (Internet of Things, or internet connected toasters), the capabilities of having human-computer interactive elements has gone through the roof. Our abilities for having real-time physical feedback for certain user interactions.

Take, for example, the brig. In the old Voyager, there was just an array of fluorescent blacklights, switched from the control room, indicating a force field. The security officers would have special sashes which allowed them to walk through the force field with anything they might have been carrying. To get though the field, you have to have a sash. However, the lights remained on whenever anyone stepped through them - there was no indication that the forcefield did anything.

In the new ship, we are going to be placing a Raspberry Pi microcomputer in the wall adjacent to the brig. Connected to it will be an RFID (Radio Frequency ID, or micro ID - they put these things in credit cards and your pets) reader and a camera. The RFID reader will be programmed to detect specific RFID which will be sewn into the two security sashes in the new security uniforms. To enter the brig, security will have to badge the scanner to deactivate the force field (since the brig lights are computer controlled, it will be totally automatic). A sound effect will play as the forcefield dims. They can then throw the bad guys in, badge again, and the force field will flicker back to life.

What if someone breaches the forcefield? Well, that’s what the camera is for. It will be constantly scanning to see if there is someone or something in the way of the forcefield. If it notices something in the path, it sends a signal to the brig, which will play a sound effect and flicker, as if the force field was aggravated. That should be enough of an effect to keep someone from stepping through.

Engineering panels throughout the ship will also interface with the main computer systems in various ways. Power conduits which affect the lighting, a set of self-destruct buttons which must be pushed simultaneously to work properly, video conferencing; The point is that we can connect just about anything we want to the system and, with the right code in place, it will just work.

Eventually we finished constructing the Voyager. You can visit them today, and you totally should. A lot of work went into it, and still goes into it. It’s really come together.

It wasn’t without its challenges and problems. One of the first casualties was Flint, the JavaScript-based controls which were developed in tandem with the simulator. These controls were intended to be the brains of the entire simulator. They would controls the lights, sounds, music, ambiance, and naturally the station controls. It would be an integrated simulator like no other. Or so we hoped.

Most of the features were developed into Flint, but unfortunately it missed the mark. It was super complicated to configure, difficult to use, and not reliable. We were so interested in building these innovative features that we didn’t think through how to do it right. We didn’t have any attention focused on the actual station controls. Even worse, we didn’t pace ourselves. Without a fun environment to work in and with a plethora of pressures on us, Brent and I quickly burnt out, and progress on Flint slowed to a crawl.

The simulator was able to open with most of its show controls in place and with a backup set of controls, but it wasn’t ideal. Neither of us were satisfied with the results, but there wasn’t much to be done.

Or was there?

As it turns out, building spaceship simulator controls is a really great way to learn new things. I learned how to program when I build the Revolution/LiveCode simulator controls back in the day; I learned more about JavaScript, HTML, and Node by developing Flint. There were some new technologies coming out that I was interested in pursuing - specifically React, Elixir, and GraphQL. Maybe I could start making some controls, you know, just to learn these techs. Who knows where it would go?

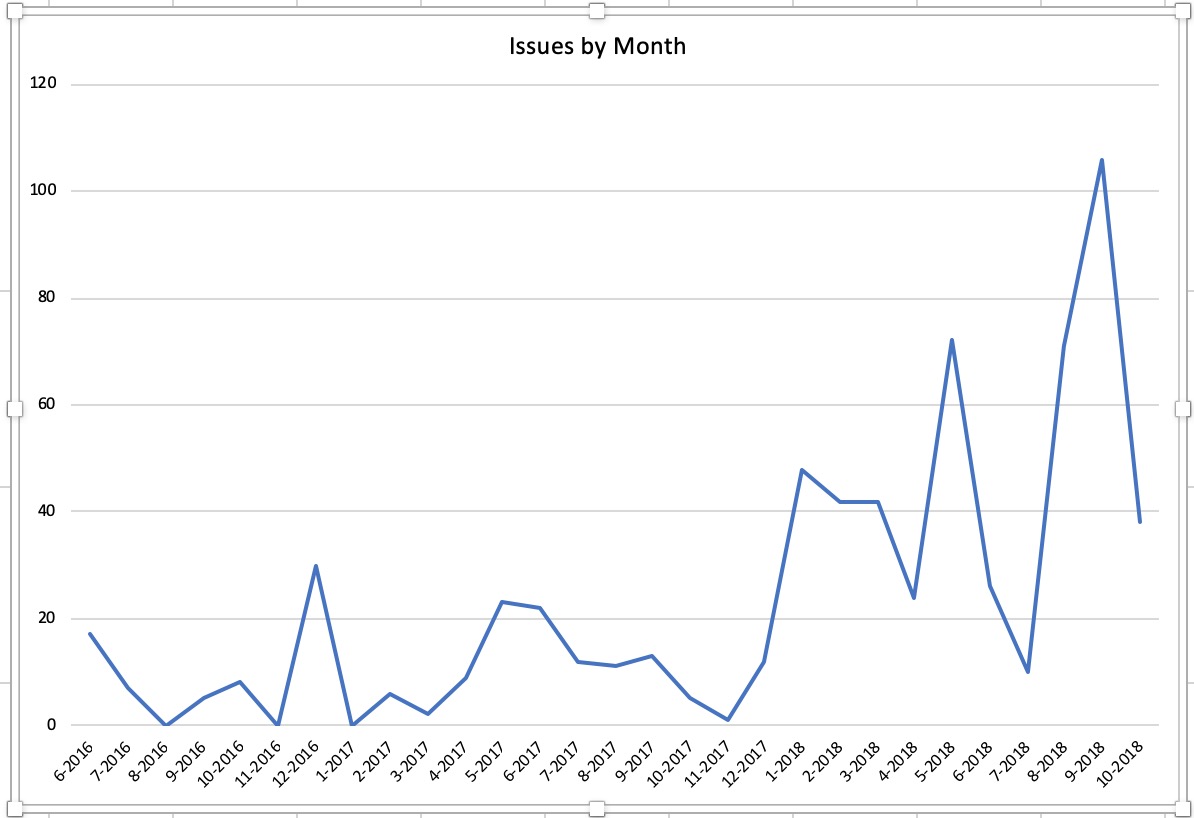

I started this project in June of 2016, I started working on this project, dubbed Thorium. One of the biggest struggles of the Flint project was the fact that the features and direction of the project were being dictated by a creative team that couldn’t come to consensus. Without knowing what the roadmap was, it was impossible to make meaningful progress. I wanted to avoid those pitfalls by keeping the project to myself. This was to be a learning opportunity.

Progress at first was slow, but that’s mainly because I was learning so much. Elixir was an entirely different paradigm; GraphQL was similar. It took me a long while to finally figure out how everything was supposed to work together, but I got a working prototype put together.

There were a couple of ways I wanted to build on previous simulator controls:

- It should be totally composable. This was brought to the table by Mercury, which allowed flight directors to distribute cards to whatever stations they want.

- It should support effects controls, like sound effects, lighting, viewscreens, and more. Flint was the first to pioneer centralized effects.

- It should have all of the cards and screens necessary to work for any current or future ship. It should be possible to use Thorium for a small shuttle, a larger battleship, a carrier, or even a submarine. All of these should be possible.

- It should also be a platform for innovating new features and screens. That was a huge piece of the reason why Flint was built - to create new screens for the Farpoint universe. Thorium should be able to meet that expectation.

- It should support multiple themes, so each simulator can have its own look and feel.

I was going to approach Thorium a little bit differently though:

- It was going to be built with the latest and best technologies. Simulator controls are complicated, and in order to make them as functional and performant as possible, it would a bit of a boost.

- React makes it really easy to build complicated, state-based layouts and matched the needs of Thorium perfectly.

- GraphQL make it very easy to get specific data from a server on-demand. The Subscription features which GraphQL brings to the table make it insanely easy to do realtime data.

- I was going to focus this project on learning first, marketing later. The primary of purpose was to learn; nothing more, nothing less. Having other people involved in the project would easily take away from that educational environment.

- I wanted to build a team to help work on the controls. This is actually the reason I dropped Elixir and Docker in favor of Node for the backend. Elixir is cool, and would totally fit the needs of Thorium. On the other hand, it’s a bit harder to learn and isn’t as ubiquitous as Node making it more difficult for people to pick up. Using Node makes it easier for others to jump in and contribute. Also, in 2016, the GraphQL Subscriptions story was much better in Node than Elixir (it’s much better now than it was).

- I wanted to actually finish the controls. To me, that meant being able to run a simulation from start to finish with a real crew in a real simulator. Flint’s failure still stung, so I wanted to make sure these controls were completed.

Thorium was going to change a couple of things about simulator controls too:

- All previous simulator controls are simulator-centric. All of the state is centered in the simulator. This doesn’t work in the era of long-duration missions. Thorium would be more flight-centric, allowing for pausing, concurrent flights, and coming back to flights later.

- The flight director should have as much power and control as possible. Their job is to make sure the crew has the best time possible during their flight. Everything in Thorium should either make it easier for the flight director to give the crew a great time, or remove distraction from the flight director, or both.

- Missions would be very centralized, allowing for the viewscreen to be connected to the controls and for actions like sending long range messages and answering scans to be automated by the timeline.

- Flight directors could be assisted by actionable notifications through the Core Feed, a new feature that hopefully would make it easier for the flight director to do their job.

- While it wasn’t the intention to begin with, Thorium was eventually open-sourced, allowing anyone to contribute to Thorium, or even fork it and do their own thing with it. This would make it easier for outside contributors to help build it.

Fast-forward a year and I did it. I built a set of simulator controls. I’ll talk more about the process I went through in later blog posts, but the point is that I had come to the point where Thorium was ready to be shown off. Up to this point, only a select few people knew about these controls. I started having one-on-one meetings with the space center directors, showing them the controls, and getting feedback.

I also started doing test flights, which was great fun. It allowed me to bring my family and friends to the space center to finally show off what I’ve been working on for so long. The feedback from the test flights was great. People were excited about the controls and gave mostly positive feedback about the experience. (Fortunately, they didn’t notice all of the major problems happening behind the scenes).

I didn’t expect it when I first opened up Thorium to the space centers, but my learning process was not complete. Customer support and project management were the next things I would learn more about, and I wasn’t even expecting it. Working with the space centers to make Thorium better has been a pleasure and delight, but it hasn’t been easy. There have been a lot of issues submitted.

Thorium has been a great success in a lot of ways. It also hasn’t worked out so well in many ways. For example, I haven’t had much success in getting repeat contributors to help me work on Thorium. It was my hope that something like that could happen, but it just hasn’t worked out yet. Maybe it will someday. (If you’re interested in working on Thorium, get in touch on the Discord server!)

Interested in playing with Thorium? Check it out!.

Enjoy!